2025 WAEC Literature Answers - Education - Earboard |

|---|

(7 ) (Reply) (Create New Posts) (Go Down)

| 2025 WAEC Literature Answers by Flex: 10:21 am On May 15, 2025 |

WAEC 2025 Literature Answers are now out. To get it, simply buy MTN recharge card of N500 and send the pin together with the subject paid for to 09067385575. Don’t have money to pay? Simply share this post with all your friends writing WAEC. If we get enough shares on social media, we may post it for free. If you have already paid, click on the button below to enter your password. Click Here to View The Answers Now!

FREE ANSWERS Thursday, 15th May 2025

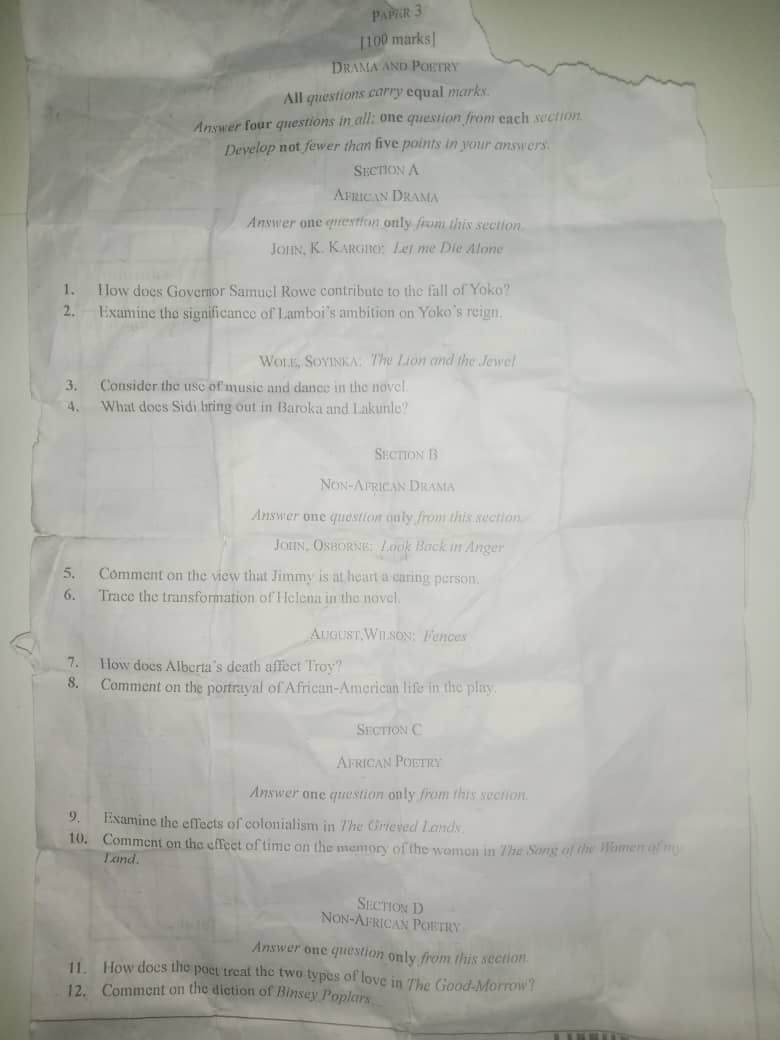

There are FOUR sections: Section A (Questions 1–4) Section B (Questions 5–8) Section C (Questions 9 & 10) Section D (Questions 11 & 12) You are required to answer ONE question from each section. We’ve done everything possible to ensure everyone writes something different. COMPLETED 💯% GOOD LUCK!

(VERSION I) (1) From the outset, Rowe establishes his dominance through the public humiliation of Chief Gbanya, Yoko’s predecessor. By fining and threatening Gbanya in front of his own council, Rowe sends a clear message: traditional rulers hold power only at the colonial administration’s discretion. This act of subjugation sets the tone for Yoko’s eventual struggle, as she inherits a leadership role already stripped of its autonomy. Unlike Gbanya, who openly resists colonial interference, Yoko attempts to navigate Rowe’s demands through diplomacy. However, Rowe exploits her willingness to negotiate, turning her strengths into liabilities. Each concession she makes—whether accepting unjust taxes or suppressing dissent to maintain peace—further alienates her from her people, who begin to view her as a collaborator rather than a protector. Rowe’s manipulation extends beyond political maneuvering; it is a form of psychological warfare. He isolates Yoko by creating impossible choices: comply with colonial demands and lose her people’s trust, or resist and face brutal repercussions. This relentless pressure erodes her mental resilience, leaving her trapped in a cycle of self-doubt and despair. Her famed diplomatic skills, once a source of pride, become tools for her undoing as Rowe weaponizes her intelligence against her. The colonial administration under Rowe operates on a foundation of systemic oppression, where native leaders are stripped of agency and reduced to mere figureheads. Compounding Yoko’s suffering is the betrayal by her own brother, Lamboi, and other elders. While their conspiracy is driven by personal ambition, it is Rowe’s destabilization of traditional hierarchies that enables their treachery. By weakening Yoko’s authority, Rowe creates a power vacuum that opportunistic figures like Lamboi rush to fill. The play underscores how colonialism doesn’t just oppress through direct force but also fractures communities from within, turning kin against kin. Yoko’s isolation becomes complete—abandoned by her people, betrayed by family, and crushed under the weight of colonial expectations. Yoko’s suicide is the tragic culmination of Rowe’s oppressive regime. In a world where resistance is futile and submission is synonymous with cultural erasure, death becomes her only escape. Her final act is not one of defeat but of defiance—a refusal to exist in a system designed to break her. Rowe’s role in her downfall is thus not merely as an antagonist but as the embodiment of colonialism’s dehumanizing machinery. His legacy is one of destruction, leaving behind a broken leader and a shattered society. Through Yoko’s tragedy, the novel exposes the insidious nature of colonial rule, where leaders like Rowe wield power not just through laws and decrees but through the deliberate dismantling of identity, community, and hope. Rowe’s contribution to Yoko’s fall is a stark reminder of the cost of imperialism—not just in land and resources, but in human lives and dignity.

(1) Rowe’s campaign against indigenous leadership begins with his calculated humiliation of Chief Gbanya, a spectacle designed to demonstrate colonial supremacy. This public degradation serves as a warning to Yoko – her power exists only at the pleasure of the British administration. When she assumes leadership, Rowe employs more subtle but equally destructive tactics. He cloaks his oppression in the language of law and order, imposing crippling fines and arbitrary regulations that force Yoko into impossible choices. Each decision to comply with colonial demands further erodes her standing with her people, while resistance invites swift retaliation. The psychological dimension of Rowe’s oppression proves particularly devastating. He manipulates Yoko through alternating currents of feigned respect and veiled threats, creating an environment of constant anxiety. His administration operates as a relentless grinding machine, wearing down Yoko’s resilience through bureaucratic harassment and the constant undermining of her authority. The colonial office becomes a chamber of slow suffocation, where every petition for fairness is met with condescension, every appeal to justice answered with fresh demands. Rowe’s most insidious achievement lies in how he transforms Yoko’s virtues into liabilities. Her intelligence, which should serve her people, becomes a tool for her manipulation. Her commitment to peace is twisted into collaboration. Her diplomatic skills are exploited to isolate her from potential allies. The colonial administration under Rowe operates as a hall of mirrors, where every move Yoko makes to protect her people only tightens the noose around her leadership. The final tragedy unfolds as Rowe’s machinations create the conditions for Yoko’s betrayal by her own kin. By systematically weakening traditional structures and fomenting discord, he ensures that when the final blow comes, it comes from within. Yoko’s suicide then stands not as surrender, but as the last act of agency available to a leader whose world has been deliberately unmade. In this, Rowe’s colonial project achieves its ultimate goal – not just the conquest of land, but the destruction of a people’s spirit.

(1) Rowe’s strategy unfolds with terrifying precision. His initial humiliation of Chief Gbanya serves as colonial theater – a public demonstration that traditional authority now answers to imperial power. When Yoko inherits this compromised position, Rowe shifts tactics. He transforms the colonial office into an instrument of psychological torment, where every interaction becomes an exercise in calculated degradation. The paperwork he demands, the meetings he summons her to, the endless bureaucratic hurdles – these are not administrative formalities but weapons in a silent war of attrition. The governor’s particular cruelty lies in his manipulation of language and protocol. He couches his oppression in the veneer of legality, dressing his demands in the language of “order” and “civilization.” When he imposes punitive fines, he calls it “taxation.” When he seizes land, he terms it “development.” This linguistic corruption leaves Yoko struggling not just against his policies, but against an entire framework designed to make resistance appear irrational. Her attempts to navigate this system with dignity only accelerate her undoing, as each compromise further erodes her standing with her people. Rowe’s colonial project reveals its true nature in its destruction of communal bonds. By fostering suspicion between Yoko and her council, by encouraging the ambitions of men like Lamboi, he executes the oldest imperial strategy – divide et impera. The breakdown of trust within the Mende leadership doesn’t happen by accident; it is the inevitable result of a system engineered to replace solidarity with self-interest. When Yoko finds herself isolated, it represents not her failure as a leader, but the success of Rowe’s systemic sabotage. In the play’s devastating conclusion, Yoko’s suicide transcends personal tragedy to become political statement. Her death lays bare the fundamental truth of colonial occupation – that it offers native leaders no survivable position. Rowe’s administration has carefully eliminated every possible outcome except surrender or destruction. That Yoko chooses the latter becomes her final act of defiance, a refusal to participate in her own humiliation. The governor’s triumph is thus revealed as profoundly hollow – he breaks the leader but cannot contain the meaning of her resistance. Through this harrowing narrative, Let Me Die Alone exposes colonialism not as a temporary political arrangement but as a machine for the systematic destruction of human dignity. Rowe’s role in Yoko’s fall demonstrates how imperial power operates not through dramatic confrontations but through the slow, relentless pressure of bureaucratic violence, leaving its victims with no enemy to fight and no ground to stand upon.

(1) From the moment Yoko assumes power, Rowe wages a silent war against her sovereignty. His weapons are not guns or chains, but documents and decrees. Each colonial edict serves as a surgical strike against her authority – land appropriations disguised as “development projects,” extortionate taxes framed as “civil contributions,” arbitrary regulations presented as “good governance.” The brilliance of Rowe’s strategy lies in its deniability; he creates a system where oppression wears the mask of progress, making resistance appear backward and unreasonable. The governor’s psychological warfare reaches its zenith in his manipulation of Yoko’s time and agency. He summons her for endless meetings at his convenience, keeping her waiting for hours, dismissing her concerns with patronizing formality. These calculated humiliations serve a dual purpose: they drain her energy while demonstrating to her people the impotence of their leader. Rowe understands that to break a community, one must first break its symbol of resistance – and he transforms Yoko’s very presence into a living testament to colonial dominance. Rowe’s masterstroke comes in his corruption of language itself. He redefines Yoko’s virtues as weaknesses – her compassion becomes sentimentality, her wisdom becomes cunning, her diplomacy becomes duplicity. By controlling the narrative, he ensures that every action Yoko takes can be interpreted as evidence of her unfitness to rule. The colonial office becomes an echo chamber where reality bends to Rowe’s will, leaving Yoko gasping for truth in an atmosphere of manufactured doubt. The tragedy reaches its climax as Rowe’s machinations achieve their intended effect: the complete isolation of the ruler from the ruled. When Yoko’s own people turn against her, it represents not their failure but the terrifying efficiency of colonial mind-alchemy. Rowe has succeeded where brute force might have failed – he has convinced the Mende to participate in their own subjugation. In her final moments, Yoko’s suicide transcends personal despair to become an act of radical testimony. Her death screams what colonial records will never acknowledge: that some systems of power are designed to make survival itself a form of surrender. Rowe’s victory is thus revealed as inherently fragile, built on foundations of lies that cannot withstand the truth of Yoko’s final, terrible choice. The colonial edifice remains standing, but its moral bankruptcy stands exposed – a monument not to civilization, but to the lengths empires will go to break what they cannot understand.

(VERSION I) (2) One of the major impacts of Lamboi’s ambition on Yoko’s reign is the manipulation of public perception. He works behind the scenes to portray Yoko as incapable and unfit to lead, feeding on the conservative belief that a woman should not hold such a powerful position. By sowing seeds of doubt among the elders and townspeople, Lamboi weakens Yoko’s support base and isolates her emotionally. His schemes turn allies into skeptics, undermining the unity she desperately needs to govern effectively. Lamboi’s ambition also leads to direct sabotage. In collaboration with Musa, the deceitful medicine man, Lamboi engages in rituals and plots that create fear and confusion within the community. His willingness to lie, deceive, and manipulate traditions in order to push his own agenda reveals the destructive power of unchecked ambition. These schemes not only disrupt Yoko’s rule but also erode the trust between the ruler and the ruled. Furthermore, Lamboi’s actions indirectly lead to Yoko’s psychological downfall. The constant pressure, betrayal, and resistance she faces take a toll on her mental health. The loneliness of power, coupled with Lamboi’s schemes, causes her to question her decisions and feel abandoned by the very people she seeks to lead. In the end, it is not an external war that breaks Yoko, but the internal sabotage led by Lamboi’s thirst for power. Lamboi’s ambition highlights the broader themes of gender inequality and the resistance to change in traditional African societies. His refusal to accept Yoko’s leadership simply because she is a woman reflects societal fears about female authority. His ambition not only undermines her reign but serves as a mirror to the cultural and political challenges faced by women in leadership roles. Through Lamboi’s actions, the play critiques the destructive nature of envy and the dangers of prioritizing personal ambition over communal good. His role is a reminder of how internal opposition can be more fatal than any outside threat.

(2) Early in her reign, Lamboi uses subtle manipulation to cast doubt on Yoko’s competence. Rather than openly challenging her, he quietly influences other elders and political figures to question her suitability for the throne. He capitalizes on cultural prejudices and societal expectations, framing Yoko’s emotional responses and decisions as signs of weakness. This not only damages her reputation but creates an atmosphere of suspicion and isolation around her, making governance increasingly difficult. Lamboi’s partnership with Musa, the deceitful medicine man, significantly escalates his campaign against Yoko. They use spiritual manipulation and traditional superstitions to instill fear and discredit her leadership. Musa, with Lamboi’s encouragement, exploits the people’s trust in spiritual authority to fabricate visions and signs that work against Yoko’s decisions. Their combined efforts turn spiritual belief into a political weapon, eroding the people’s confidence in their chief. The use of ritual and false prophecy illustrates how ambition can corrupt both politics and culture when driven by selfish intent. As Yoko becomes more isolated, Lamboi’s schemes continue to weigh heavily on her psychologically. Her reign becomes a lonely struggle against unseen enemies, and her inability to identify or counter Lamboi’s plots adds to her emotional exhaustion. The burden of leadership, combined with betrayal from within her own court, leads Yoko into despair. She begins to question her legitimacy and the very ideals that led her to accept the throne. Lamboi’s ambition, therefore, doesn’t just threaten her position; it shatters her confidence and will to rule. Lamboi’s ambition is ultimately significant because it exposes the fragility of leadership in a society where gender and tradition collide. His refusal to support a woman in power reflects the wider cultural resistance that women like Yoko must face. His betrayal brings to light the dangers of envy and personal ambition when cloaked in the guise of tradition. Through Lamboi, the play emphasizes how internal threats—especially those driven by pride and prejudice—can be more devastating than any external conflict. His ambition is a destructive force that not only topples a reign but also extinguishes a visionary leader’s spirit.

(2) Rather than confront Yoko directly, Lamboi operates behind the scenes, masking his envy with false allegiance. He cleverly manipulates others, particularly Musa, the manipulative medicine man, to execute his plans while he remains in the background. This strategy allows him to avoid suspicion while exerting great influence over the people and the palace. His ambition fuels Musa’s deceptive spiritual rituals, which are used to instill fear, misguide the public, and manipulate sacred customs against Yoko’s authority. A significant impact of Lamboi’s ambition is the erosion of public trust in Yoko’s leadership. By encouraging false prophecies and promoting fear-based manipulation, he creates unrest among the people. Yoko is portrayed as a ruler out of touch with the will of the gods and the expectations of the people, which shakes the very foundation of her legitimacy. This loss of credibility weakens her emotionally and politically, leaving her isolated in a role that demands strong alliances and public confidence. The psychological toll on Yoko cannot be overlooked. The constant pressure, betrayal, and loneliness she experiences under Lamboi’s secret attacks take a heavy emotional toll on her spirit. Her initial strength and resolve begin to diminish as her leadership becomes increasingly undermined. Her eventual despair is not the result of military failure or external rebellion, but the consequence of internal sabotage orchestrated by someone she trusted. This highlights the emotional cruelty embedded in Lamboi’s ambition. Moreover, Lamboi’s actions reflect the broader societal tensions surrounding gender, power, and tradition. His inability to accept Yoko’s leadership is not just personal but representative of a patriarchal worldview that sees female leadership as unnatural or temporary. His ambition, therefore, serves as a symbolic force that challenges not only Yoko’s reign but the very idea of women in authority. The damage he causes speaks to the dangers of letting tradition be weaponized by individuals seeking personal gain. In the end, Lamboi’s ambition does not only remove Yoko from the throne—it extinguishes her passion, silences her vision, and denies her the support she deserved. His covert pursuit of power stands as one of the greatest tragedies in the play, proving how ambition rooted in envy and prejudice can destroy both a leader and the hope they represent.

(2) Instead of openly challenging Yoko, Lamboi chooses to undermine her through manipulation and deceit. He aligns himself with Musa, the manipulative spiritualist, using religious influence to create fear and doubt in the minds of the people. Lamboi understands that in their culture, spiritual legitimacy is critical to political power. By using Musa to plant fake visions and spiritual warnings, he is able to destabilize Yoko’s authority without exposing himself as a traitor. This strategy highlights how ambition can disguise itself in loyalty while working against the very foundation of trust. Lamboi’s ambition also serves to isolate Yoko emotionally and politically. The manipulations gradually cause her allies to grow suspicious or distant, leaving her to lead without strong support. This loneliness weighs heavily on Yoko, who already faces the cultural challenge of being a female chief in a male-dominated society. With Lamboi quietly turning others against her and chipping away at her confidence, Yoko begins to lose the emotional resilience needed to withstand the demands of leadership. His ambition therefore functions not just as a threat to her power but as a direct attack on her psychological well-being. Moreover, Lamboi’s ambition reflects the larger issue of patriarchal resistance to female leadership. He is not just jealous—he is deeply opposed to the idea of a woman having authority over men. His behavior underscores the societal prejudice that views women as too weak or emotional to lead. Lamboi exploits this belief system for his gain, rallying support through shared doubt rather than genuine merit. Through this, the play critiques how ambition and misogyny can work hand in hand to sabotage progress. In the end, Lamboi’s relentless pursuit of power strips Yoko of her strength, dignity, and hope. Her tragic death is not caused by external enemies but by the ambition of someone within her circle of trust. His significance in the play is not just in what he does, but in what he represents—a warning about the consequences of selfish ambition and the cost of betrayal disguised as tradition. Through Lamboi, Kargbo illustrates how the thirst for power can ruin not only leaders but also the future they were trying to build.

(VERSION I) (3) From the very beginning of the play, Soyinka uses dance and mime to dramatize events and express community values. In the “Morning” section, the villagers stage a mimed performance called “The Dance of the Lost Traveller,” led by Sidi and the village girls. This theatrical reenactment depicts the bewilderment of a foreign photographer who visits Ilujinle. Through this, the villagers mock the outsider’s fascination with their way of life. The scene not only provides comic relief but also underscores the tension between local traditions and foreign influences. It is a creative way for the community to reclaim the narrative of how they are perceived by the outside world. Soyinka also uses mime to reflect political and ideological conflict. Lakunle, the Western-educated schoolteacher, performs a dramatization of how Baroka, the village chief, allegedly sabotaged the plan to bring a railway to Ilujinle. Lakunle’s mime is exaggerated and theatrical, portraying Baroka as an obstacle to progress. However, his performance also reveals his failure to connect with the villagers on their own terms, reinforcing the idea that modernization cannot succeed when it is imposed disrespectfully or without understanding tradition. Another powerful use of dance occurs when Sadiku, Baroka’s head wife, rejoices after being misled into thinking that Baroka has lost his manhood. She dances and sings in celebration, symbolizing what she perceives as the triumph of women over male dominance. Yet this celebration is ironic, as it is later revealed that Baroka tricked her to test her loyalty. Here, Soyinka uses dance to reveal both character flaws and thematic irony. Finally, the mimed wrestling match between Baroka and his opponent symbolizes strength and masculine pride. The performance is designed to impress Sidi and reassert Baroka’s vitality. In the end, music and dance culminate in the final wedding celebrations, reinforcing tradition’s victory over the unrooted promises of modernity. Thus, through song, dance, and mime, Soyinka creates a vibrant theatrical world where performance becomes a form of resistance, celebration, and storytelling.

(3) The use of dance and mime becomes immediately evident in the first part of the play, where Sidi and the village girls perform a dramatized version of a foreign photographer’s visit. Known as “The Dance of the Lost Traveller,” this performance uses movement and rhythm to depict the confusion and wonder of the outsider. It reflects how the villagers see themselves through foreign eyes while also mocking those who fail to understand their culture. Through this communal dance, Soyinka emphasizes the pride the people take in their traditions and how storytelling through performance helps preserve their identity. Mime also plays a critical role in expressing ideological tensions. Lakunle, the village schoolteacher who champions Western education and progress, stages a theatrical mime to criticize Baroka, the village chief. In this scene, he tries to expose Baroka’s role in blocking the proposed railway project. However, the exaggeration and drama in Lakunle’s performance only highlight his lack of influence in the village. His failure to inspire real change through his modern ideas underscores the theme that modernization, when poorly rooted in local understanding, often falters. Another moment where dance takes center stage is when Sadiku, Baroka’s head wife, celebrates what she believes is his downfall. After being told that the Bale has become impotent, she joyfully sings and performs a “victory dance” in the village square. This scene is not only humorous but also deeply revealing of the character’s sense of triumph and the shifting gender dynamics in the play. Yet, the revelation that she was deceived adds an ironic twist to her celebration, showing the cunning and resilience of Baroka. The mimed wrestling match between Baroka and a younger man, watched by Sidi, serves to affirm the Bale’s physical vitality and dominance. This performance is strategic—Baroka uses it to reinforce his traditional power and appeal to Sidi’s admiration. In the final act, music and dance bring the community together, celebrating Sidi’s decision to marry Baroka and symbolizing the continued strength of tradition over untested modern ideals. In all, Soyinka masterfully uses music and dance to enrich the play’s message, giving life to its themes while anchoring the story in Yoruba performance traditions.

(3) One of the earliest and most striking uses of performance in the play is found in the villagers’ reenactment of the stranger’s arrival. In this mimed episode, Sidi and the village girls perform “The Dance of the Lost Traveller,” a light-hearted yet significant piece that shows the confusion and strangeness of a white man trying to understand their way of life. The villagers tell their own story using song and movement, reclaiming their identity from the outsider’s lens. This dramatization not only entertains but also reveals the pride the community takes in its traditions, and subtly critiques the Western tendency to misunderstand African societies. Later in the play, mime is again used to express conflict and satire, particularly when Lakunle performs a dramatic piece about the proposed railway. His exaggerated gestures and theatrical narration are meant to accuse Baroka of sabotaging the project. However, the scene also shows Lakunle’s limitations as a character; despite his modern education, he struggles to influence the villagers and fails to connect with them emotionally. The mime ends up reinforcing the idea that modernization, when separated from cultural understanding, is hollow. Soyinka also uses dance as a vehicle for emotional expression and irony. When Sadiku believes Baroka has lost his manhood, she bursts into dance and song, celebrating what she thinks is the defeat of male power. This moment is comedic and revealing, showing her desire to see women triumph over patriarchy. But the celebration is premature—Baroka has only pretended to be impotent, turning Sadiku’s victory dance into a moment of irony and showing his strategic control over others. The final celebration in the play brings together music, dance, and song as Sidi marries Baroka. This conclusion, rich with rhythm and communal joy, affirms tradition’s continued dominance. Soyinka, through these performances, paints a vivid portrait of a society negotiating change while rooted in its cultural heritage. Music and dance become the heartbeat of Ilujinle, embodying its voice, its struggles, and its resilience.

(3) One of the most significant uses of music and dance in the play is in the re-enactment of past events. For example, during the performance of the “lost traveler” story, the villagers use song, mime, and dance to recreate how Sidi’s pictures ended up in a foreign magazine. This dramatized storytelling captures the audience’s attention while preserving the oral tradition of passing down knowledge. Music and dance here serve not just to entertain, but to educate and unite the community around shared history and values. Music and dance are also used to express character traits and emotions. For instance, Baroka, the village chief, uses drumming and traditional rhythms to display his vitality and cunning nature. His ability to participate in dances and traditional ceremonies positions him as a man still in touch with his culture and people. In contrast, Lakunle, the Western-educated schoolteacher, is often disconnected from the musical and dance aspects of village life. His awkwardness around these performances symbolizes his alienation from the traditional world he wishes to change. Another important role of music and dance is in courtship and romantic rivalry. The dances performed during Sidi’s interactions with Baroka and Lakunle reflect the competition between tradition and modernity. While Lakunle avoids bride-price and embraces Western ideas, Baroka expresses his intentions through more traditional and symbolic performances. Music and dance here do not just show affection—they become a battleground where cultural ideologies are contested. Music and dance also reflect celebration and communal identity. At several points in the play, the villagers use singing and dancing to mark important moments, such as festivals or significant decisions. These performances strengthen the sense of belonging among the characters and reflect the importance of collective expression in African societies. Through them, Soyinka shows that culture is not just preserved in words, but in movement and rhythm. In conclusion, Wole Soyinka’s use of music and dance in The Lion and the Jewel is both symbolic and functional. It enriches the storytelling, highlights cultural conflicts, expresses emotion, and reinforces traditional values. These elements turn the play into more than just a script—it becomes a celebration of African heritage and the enduring power of communal performance.

(VERSION I) (4) Sidi’s physical beauty and youthful confidence expose Lakunle’s intellectual arrogance and detachment from reality. Although he claims to love her, Lakunle is more fascinated by the idea of modernizing her than by understanding her as a person. His refusal to pay her bride price, which he considers an outdated custom, reveals not just his modern ideals but also a patronizing attitude. Instead of respecting Sidi’s cultural identity, he tries to impose Western values upon her. In her response, Sidi mocks Lakunle’s speech, laughing at his exaggerated English vocabulary and romantic theories. Her rejection of his ideology shows that she is not ready to abandon her roots simply for empty promises. With Baroka, Sidi draws out a different set of traits, those of strategy, patience, and manipulation. When she initially rejects him, Baroka does not react with anger but instead with calculated calm. Her rejection challenges his pride, and it spurs him to devise a plan that involves faking impotence to lure her into his trap. Sidi’s self-assurance, sparked by her growing fame after her pictures appear in a magazine, blinds her to Baroka’s deeper intentions. By the time she visits him to mock his supposed weakness, she falls into his carefully laid scheme. Her effect on Baroka reveals his mastery of tradition not just as a static concept, but as a tool of influence. He uses his image as an old chief not to dominate directly, but to outwit and seduce. Sidi’s pride, innocence, and vanity become the very traits Baroka uses to win her over. She becomes the prize that proves his continuing relevance in a changing world. Thus, Sidi exposes Lakunle’s ineffectiveness as a reformer and Baroka’s adaptability within tradition. She becomes the stage on which the contest between past and future is played out. While she starts as the village jewel admired for her beauty, she ultimately helps define the true strengths and flaws of both suitors, revealing who truly understands power, love, and the pulse of the society they live in.

(4) In Lakunle’s case, Sidi highlights his impracticality and obsession with modern reforms. He claims to love her, but his love is buried beneath a desire to civilize her. His refusal to pay the bride price is not based on respect but on a condescending belief that African customs are barbaric. Sidi, who understands and values her traditions, challenges this perspective by insisting that her worth must be acknowledged in accordance with local customs. Her sharp tongue and playful teasing expose Lakunle’s ignorance and his inability to connect emotionally with the culture he seeks to change. Lakunle’s inflated vocabulary and frequent quoting of foreign ideas only further show his detachment from reality. Sidi, unimpressed, reduces his arguments to meaningless chatter. In doing so, she brings out his weaknesses: pride, foolishness, and an unrealistic approach to societal change. Rather than being a reformer with practical solutions, he becomes a comic figure in Sidi’s eyes, full of ambition but lacking depth. With Baroka, Sidi evokes traits of calculation and subtle power. Initially, she mocks his age and believes that she is beyond his reach. Her growing confidence after being featured in a magazine leads her to believe she is more valuable than ever. This pride, however, is what Baroka exploits. He carefully stages a scene, pretending to be impotent, knowing that Sidi’s curiosity will lead her to confront him. His reaction to rejection is not aggression but careful plotting. Sidi’s impact on Baroka reveals his strategic intelligence and his deep understanding of human behavior. He does not challenge her directly but creates a situation in which her pride becomes her undoing. Through her, we see Baroka’s ability to adapt and manipulate, proving that tradition is not always passive but can be a clever tool of influence. In the end, Sidi brings out the dreamer and idealist in Lakunle and the shrewd, adaptable realist in Baroka. Her beauty and boldness serve as the spark that exposes each man’s core, showing that tradition, when clever and patient, can outwit empty modern ambition.

(4) With Lakunle, Sidi draws out his pretentious nature and deep insecurity. Although he calls himself a modern man, Lakunle’s approach to love and change is deeply flawed. He professes affection for Sidi, but his love is laced with condescension. He sees her as someone who must be reformed rather than accepted. By refusing to pay her bride price, he tries to present himself as forward-thinking, but Sidi’s insistence on tradition exposes how little he understands her or the society they live in. Sidi reacts to Lakunle’s lofty words with sarcasm and mockery. She does not take his modern ideals seriously because he fails to live them out with sincerity or respect. Through their interactions, the audience sees Lakunle as more of a caricature of modernity than a real agent of progress. His education and language make him appear learned, but Sidi shows that he lacks emotional wisdom and cultural sensitivity. On the other hand, Sidi’s beauty and pride awaken something very different in Baroka. Her initial rejection of him challenges his authority and manhood. Yet instead of reacting with open anger, Baroka responds with a quiet and calculated plan. Sidi, full of youthful confidence, does not realize she is walking into his carefully laid trap when she agrees to visit him. Her decision to mock him for his alleged impotence becomes the very moment Baroka uses to win her. Sidi’s presence brings out Baroka’s craftiness and emotional intelligence. He uses tradition not just as a set of customs, but as a strategy. Unlike Lakunle, who talks of change but understands little, Baroka embraces change when it benefits him, using it to maintain influence. Through Sidi’s actions, the reader sees Baroka’s balance of tradition and manipulation, making him more complex than he initially appears. Sidi helps expose the essence of both men. She shows Lakunle’s ideals to be hollow and Baroka’s power to be deeply rooted in understanding people. Her role is central in revealing that true influence comes not from theories or age, but from wisdom in action.

(4) Sidi’s interactions with Lakunle reveal his obsession with Western ideals and his inability to understand local customs. He sees himself as enlightened, preaching gender equality and education, but his attitude toward Sidi often reduces her to an object of reform. His refusal to pay the bride price under the banner of civilization shows his misunderstanding of what respect means within the culture. Sidi, however, challenges him by refusing to be married without the bride price. She does not reject tradition simply because it is old; rather, she demands that her value be acknowledged within that framework. Lakunle’s flowery speech and foreign ideas amuse Sidi more than impress her. Her teasing reveals how empty and impractical his ideals are when not grounded in empathy. She becomes a mirror that reflects his lack of real understanding. By doing so, she exposes him as a dreamer who is out of touch with the community he claims to uplift. In contrast, Sidi’s relationship with Baroka reveals his patient cunning and strategic mind. When she initially rejects him, his pride is wounded, but instead of lashing out, he plots a response. Sidi’s vanity over her new-found fame becomes the opening Baroka needs. Pretending to be impotent, he lures her into a position of overconfidence. Her pride leads her to believe she is immune to his charm, but this underestimation costs her. Baroka’s success with Sidi shows his mastery of subtle influence. He is not just a traditionalist but someone who knows when to adapt and how to use perception to his advantage. Sidi’s beauty and naivety bring out his ability to manipulate situations without direct confrontation. In winning her, he affirms the enduring strength of traditional wisdom and the power of patience. In the end, Sidi reveals Lakunle as a misguided reformer and Baroka as a wise, if cunning, leader. Her role is not passive; she actively shapes the story by challenging both men, making her essential to the play’s exploration of identity, power, and cultural values.

(VERSION I) (5) One key aspect of Jimmy’s character is his intense desire for emotional honesty and connection. Although his frequent verbal assaults on Alison and those around him seem cruel, they can be seen as misguided attempts to bridge the emotional distance he feels in a world that marginalizes him. His anger towards Alison is not merely spite or hatred; it reflects his frustration with the social divide that alienates him from the more privileged classes to which she belongs. Jimmy longs to be understood and accepted on a deeper level, but his immaturity and pride prevent him from expressing this longing in a straightforward manner. The moments where Jimmy’s caring nature shines most clearly are those rare instances when he drops the mask of bitterness and embraces vulnerability. For example, after Alison suffers a devastating loss, Jimmy’s willingness to forgive and reconnect with her reveals the underlying compassion that his anger often conceals. Their symbolic “bear and squirrel” game stands out as a fragile but meaningful expression of tenderness, where they can escape social roles and communicate affection through play rather than words. This scene suggests that Jimmy’s care exists but is often hidden behind defense mechanisms and sarcasm. Even Jimmy’s affair with Helena, Alison’s friend, though ethically questionable, can be interpreted as a desperate attempt to find comfort and emotional understanding outside his troubled marriage rather than simple physical gratification. This complexity adds to the idea that Jimmy’s emotional life is fraught but sincere. Ultimately, Jimmy Porter is not a heartless man. His care is real but obscured by anger, bitterness, and the psychological wounds inflicted by a class-conscious society that limits his opportunities despite his intellect. Rather than lacking care, Jimmy is a man whose caring instincts have been distorted by pain and social frustration, making him both deeply flawed and tragically human.

(5) His obsession with emotional authenticity and deep connection, although misdirected, suggests that he yearns to be understood, loved, and appreciated in a world that continuously marginalizes and alienates him. His intense disappointment in Alison stems not purely from misogyny or class resentment, but from his perception that she, like the rest of the privileged world, cannot truly understand or share in his suffering. Yet, when she finally returns to him, stripped of her pride and broken by the loss of their child, Jimmy’s readiness to reconcile reveals the ember of compassion still burning within. It is through their bizarre yet tender animal game, the bear and squirrel, that Jimmy shows his most vulnerable side, masking care behind the safety of make-believe. This moment of escape from social roles and personal bitterness hints at a man capable of deep feeling, if only through unconventional forms. Even his affair with Helena, Alison’s friend, while morally questionable, is arguably a misguided attempt to seek emotional solace rather than mere physical satisfaction. Despite his flaws and contradictions, Jimmy is not entirely devoid of humanity; he is a man whose caring nature is obscured by anger, pride, and the psychological scars of a society that offered him education but denied him opportunity. In the end, Jimmy is not heartless, but heart-hardened, a man whose care, though real, is tragically misshapen by the world around him.

(5) Growing up in a working-class background and facing early trauma, including the death of his father, has left Jimmy emotionally scarred and socially alienated. His relationship with Alison is turbulent, marked by frequent arguments and harsh criticisms, but these moments can also be read as misguided attempts to communicate his deeper frustrations and fears. Jimmy’s constant need for honesty and emotional intensity indicates that he cares deeply about authenticity in relationships, even if his approach is often destructive. The complexity of Jimmy’s care is most visible in his interactions with Alison during moments of crisis. When Alison suffers loss and vulnerability, Jimmy shows a readiness to forgive and reconnect, which reveals his capacity for compassion beneath the anger. Their “bear and squirrel” game is a poignant scene where Jimmy’s caring side emerges through playful intimacy, breaking through the barriers built by social expectation and personal bitterness. This imaginative escape suggests that Jimmy longs for closeness and affection, even if he struggles to express it conventionally. Jimmy’s affair with Helena also adds layers to his character. While morally ambiguous, it can be interpreted as an expression of his emotional isolation and his search for comfort and understanding outside the confines of his strained marriage. This reflects Jimmy’s complicated need for emotional support, rather than a simple lack of care. Lastly, Jimmy Porter’s character is marked by contradictions: he is abrasive and often cruel, yet underneath lies a man shaped by pain, social injustice, and unmet emotional needs. His care is real but tangled in anger, pride, and frustration, which sometimes blinds him to healthier ways of showing affection. Rather than being uncaring, Jimmy is a deeply human figure whose love is obscured by the wounds inflicted by both society and his own emotional struggles. This makes him a tragic and compelling character, struggling to connect in a world that often misunderstands him.

(5) The play situates Jimmy within a post-war Britain where class divisions are deeply entrenched, and as a working-class intellectual, Jimmy feels both marginalized and misunderstood. His bitterness toward Alison and others often arises not from cruelty for its own sake, but from a desperate need to be seen and emotionally connected. His verbal assaults, though painful, are frequently expressions of frustration with a society that denies him dignity and opportunity, as well as with his own inability to communicate his feelings more gently. Despite his abrasive nature, Jimmy’s care for Alison is evident in moments when the emotional walls between them briefly fall away. After Alison experiences a personal tragedy, Jimmy’s willingness to forgive and reconcile reveals the tenderness that lies beneath his anger. Their shared “bear and squirrel” game is a rare moment of intimacy, where Jimmy’s protective instincts surface in a playful and gentle manner, highlighting his yearning for closeness and mutual understanding. Jimmy’s affair with Helena, while morally complicated, also exposes his deep loneliness and need for emotional comfort. It is less about betrayal and more about his struggle to cope with feelings of isolation and his fractured relationships. This complexity shows that Jimmy’s caring nature is often obscured by his emotional turmoil and social bitterness, rather than absent. Ultimately, Jimmy Porter is a deeply flawed character whose rough exterior conceals a genuine, if troubled, capacity for care. His anger and cruelty mask a man hurt by societal rejection and personal loss, struggling to express love in a world that seems indifferent to his pain. He is not devoid of feeling; rather, his care is tangled in pride, frustration, and a yearning for connection that makes him a profoundly human and sympathetic figure. Jimmy’s character challenges the notion that anger and care are mutually exclusive, illustrating how pain can complicate the expression of love.

(VERSION I) (6) However, Helena’s character undergoes a significant and ironic transformation. After successfully convincing Alison to leave Jimmy—even arranging for Colonel Redfern to take her away—Helena does not exit the scene as one might expect. Instead, she remains in the household and, in a startling reversal, becomes Jimmy’s mistress. This shift exposes the contradictions in her moral stance. The same woman who condemned Jimmy’s behavior now engages in an affair with him, taking over Alison’s domestic role as his lover and housekeeper. Her earlier condemnations of Jimmy’s cruelty are undermined by her willingness to step into the very situation she warned Alison against. Helena’s relationship with Jimmy reveals her complex motivations. While she initially appears self-assured, her actions suggest deeper insecurities and desires. She engages in intellectual battles with Jimmy, displaying a fascination with his raw, unfiltered anger—a stark contrast to her polished middle-class demeanor. Their dynamic becomes one of mutual provocation, with Helena both challenging and being challenged by Jimmy’s intensity. Yet, despite her apparent control, she ultimately becomes another casualty of Jimmy’s emotional warfare, trapped in the same cycle she once urged Alison to escape. The return of Alison marks the final stage of Helena’s transformation. Confronted with the reality of her actions, she is forced to reckon with her own hypocrisy. Her decision to leave Jimmy’s flat is framed as a moral awakening, but it also highlights her inability to fully escape the middle-class values she claims to uphold. Her departure is less about genuine remorse than about self-preservation, as she retreats from the chaos she once sought to control. Osborne uses Helena’s arc to critique the performative nature of morality, particularly among the middle class. Her journey from critic to participant exposes the fluidity of principles in the face of desire and convenience. By the play’s end, Helena emerges as a far more ambiguous figure than she first appeared—a woman whose certainties crumble when tested, revealing the same vulnerabilities she once scorned in others. Her transformation serves as a mirror to Jimmy’s own contradictions, illustrating how easily conviction can give way to compromise.

(6) Yet Helena’s character undergoes a profound and unsettling transformation that exposes the contradictions within her moral framework. In a startling reversal of roles, after successfully orchestrating Alison’s departure by summoning Colonel Redfern, Helena doesn’t exit the scene as one might expect. Instead, she remains in the household and becomes intimately involved with Jimmy himself, taking over both Alison’s place in his bed and her domestic duties. This dramatic shift reveals the fluidity of Helena’s professed values – the woman who condemned Jimmy’s cruelty now willingly enters the very situation she warned Alison against. The complexity of Helena’s character emerges most vividly in her evolving relationship with Jimmy. Their interactions develop into a dangerous dance of intellectual provocation and s****l tension, with Helena demonstrating an unexpected fascination with Jimmy’s raw, unfiltered anger. She matches his verbal assaults with her own brand of cutting remarks, revealing a capacity for cruelty that mirrors Jimmy’s own. The ironing scene becomes particularly symbolic – as Helena assumes Alison’s place at the ironing board, she physically embodies the role she has psychologically adopted, completing her transformation from critic to participant. Helena’s eventual departure following Alison’s return marks the final stage of her character’s journey. Her decision to leave appears on the surface to be a moral reckoning, but closer examination reveals it as an act of self-preservation rather than genuine repentance. The middle-class morality she claims to uphold proves to be more about maintaining appearances than authentic principle. In this moment, Helena becomes a mirror reflecting the play’s central critique of societal hypocrisy. Osborne crafts Helena’s arc as a nuanced exploration of human contradiction and self-deception. Her journey from confident moral arbiter to compromised participant demonstrates how easily conviction can falter when confronted with desire and convenience. By the play’s conclusion, Helena emerges as a far more complex figure than her initial introduction suggested – a woman whose certainties crumble under pressure, revealing vulnerabilities she once scorned in others. Her transformation serves as a powerful commentary on the performative nature of morality and the fragility of social facades.

(6) The true complexity of Helena’s character emerges through her unexpected reversal of roles. After successfully facilitating Alison’s departure by summoning Colonel Redfern, she doesn’t withdraw as her moral stance might suggest. In a startling transformation, she remains in the flat and becomes Jimmy’s lover, assuming both Alison’s domestic duties and her place in Jimmy’s bed. This dramatic shift exposes the contradictions in her professed values, as the woman who condemned Jimmy’s behavior now willingly participates in the very dynamic she criticized. Helena’s relationship with Jimmy develops into a fascinating psychological duel. Their interactions evolve from initial hostility to a charged intellectual and s****l tension, revealing Helena’s unexpected capacity for matching Jimmy’s verbal aggression. The symbolic ironing scene perfectly captures her transformation – as she takes Alison’s place at the ironing board, she physically embodies the role she has psychologically adopted, completing her journey from detached observer to emotionally invested participant. The final stage of Helena’s evolution occurs with Alison’s return. Her decision to leave appears superficially as moral awakening, but closer examination reveals it as self-preservation rather than genuine repentance. The middle-class principles she claimed to champion prove to be more about maintaining appearances than authentic conviction. In this moment, she becomes a mirror reflecting the play’s central themes of hypocrisy and self-deception. Helena’s narrative trajectory stands as a nuanced exploration of human contradiction. Her transformation from confident moral authority to compromised participant demonstrates how easily principles can bend when confronted with desire and convenience. By the story’s conclusion, she emerges as a far more complex figure than her initial introduction suggested – a woman whose certainties crumble under pressure, revealing vulnerabilities she once scorned in others. Her journey serves as a compelling commentary on the fluid nature of morality and the fragility of social facades.

(6) From the outset, Helena is disturbed by the constant verbal aggression and emotional cruelty Jimmy directs at Alison. She views Jimmy as intolerable and uncouth, someone unworthy of her friend’s love or patience. As an outsider, she quickly forms strong opinions and decides to intervene in what she perceives as a destructive marriage. Her intervention becomes more than verbal persuasion—she goes as far as contacting Colonel Redfern, Alison’s father, to take Alison away from Jimmy. This act highlights Helena’s boldness and her belief in her own moral authority. At this point, she positions herself as a savior, someone who upholds decency and is willing to challenge what she sees as abusive behavior. However, Helena’s moral position becomes deeply questionable when she remains in Jimmy’s flat after Alison’s departure and becomes intimately involved with him. She not only assumes the role of Jimmy’s mistress but also functions as his housekeeper, replacing Alison both emotionally and practically. This unexpected turn reveals the conflict between Helena’s moral principles and her personal desires. Despite her earlier judgments about Jimmy’s character, she finds herself drawn to him, both physically and emotionally. Her actions betray a hypocrisy that calls into question the strength of her supposed moral superiority. It becomes clear that Helena is not immune to the chaos and passion she once condemned. The final stage of Helena’s transformation occurs when Alison returns to Jimmy’s apartment, broken and emotionally drained. Helena is confronted with the reality of her choices and the pain they have caused. Her remaining sense of decency and middle-class values resurfaces, prompting her to end her relationship with Jimmy and leave. She recognizes the inappropriateness of her actions and, in her own way, tries to restore some order by stepping away from the situation. Her departure is not just a physical act but a symbolic retreat into the moral codes she once upheld. Helena’s journey in the play reveals a woman torn between righteousness and emotional vulnerability. Her transformation from a poised moral observer to a deeply conflicted and flawed participant mirrors the broader themes of instability, hypocrisy, and human weakness in Look Back in Anger. Through Helena, Osborne illustrates how the lines between right and wrong often blur when emotions are involved.

(VERSION I) (7) With Alberta gone, Troy is no longer shielded from reality. He is now responsible for Raynell, the child born out of the affair. The presence of Raynell is a constant reminder of his betrayal, and this marks the beginning of a new form of loneliness in Troy’s life. Rose, his wife, agrees to raise the child but refuses to continue the emotional role of being Troy’s partner. Her decision creates a significant emotional gap between them that Troy cannot repair. Troy’s relationship with his son Cory also worsens after Alberta’s death. Already strained by Troy’s oppressive parenting and refusal to support Cory’s football dreams, their bond breaks completely. Troy’s attempt to protect Cory from disappointment, rooted in his own bitter experiences, only succeeds in driving the boy away. The emotional walls around Troy grow thicker, and he begins to live a life of increasing solitude. Her death also exposes the fragility of the identity Troy had built for himself. He always tried to present himself as strong and in control, but Alberta’s death lays bare the emptiness of this image. The illusion of power and authority he once held crumbles, revealing a man deeply wounded by his past and confused about his future. While Alberta’s death does not bring immediate transformation to Troy’s character, it sets the stage for his eventual downfall. It brings his flaws and mistakes into focus, both for himself and for those around him. He is left to reflect, though quietly, on the damage he has done. In this way, Alberta’s death acts as a moment of reckoning, a symbol that no matter how hard he tries, Troy cannot escape the emotional consequences of his choices. Her death closes the door on fantasy and forces him to live in the world he has broken.

(7) Alberta’s death brings Troy’s secret life crashing into his household. It exposes the betrayal he had long concealed from Rose, leading to a deep emotional separation between them. Rose agrees to raise Raynell out of compassion, but she firmly distances herself from Troy as a wife. Her decision to remain only in the role of mother, not partner, leaves Troy without the emotional support he had once taken for granted. This loss is not physical, but spiritual and emotional, one that isolates Troy in his own home. The strain on Troy’s family life deepens. His son Cory, already hurt by Troy’s refusal to support his football dreams, finds further reason to reject his father. Troy’s authoritarian attitude, combined with his hypocrisy, pushes Cory to the point of rebellion. With Rose emotionally distant and Cory estranged, Troy becomes increasingly isolated, surrounded by silence rather than the voices of family. Alberta’s death also forces Troy to face a difficult truth: the life he imagined with her, one filled with freedom and affection, was never sustainable. She had represented the possibility of happiness outside his marriage, but with her gone, that possibility dies with her. He is left only with the consequences, a child he must raise, a marriage that is emotionally broken, and a son who no longer respects him. Though Alberta’s death doesn’t change Troy overnight, it symbolizes the collapse of everything he once used to hide from his pain. The control he tried to maintain over his life slips away, leaving a man who must live with the weight of his choices. It becomes clear that Alberta’s death is not just a personal loss, it is a moment of truth. It strips away Troy’s defenses and leaves him alone with the reality he created, one filled with regret, broken relationships, and emotional ruin.

(7) The first and most immediate effect of Alberta’s death is the arrival of Raynell, the child she bore with Troy. Her birth forces Troy to confront the reality of his betrayal to Rose, who responds with dignity but firm emotional separation. Rose agrees to raise the child but tells Troy that she will no longer be his wife in the same way. That conversation marks the beginning of Troy’s emotional solitude. Though he still lives in the same house, his connection to Rose is broken. The damage also extends to his son Cory. Already frustrated by Troy’s refusal to let him pursue a football scholarship, Cory sees Troy’s hypocrisy and emotional cruelty more clearly after Alberta’s death. Their relationship deteriorates rapidly, eventually leading to a physical and emotional break between father and son. Troy’s attempts at discipline, once rooted in fear and control, now seem hollow and harsh in light of the mess his own life has become. Troy, once the dominant force in the household, becomes a man surrounded by emotional emptiness. Alberta’s death removes the last bit of warmth and escape in his life. With Rose and Cory both distancing themselves from him, Troy turns more inward, speaking often to death as if it were his only remaining companion. The loss pushes him closer to the edge, not just of loneliness but of a slow emotional breakdown. While Alberta’s death does not cause an immediate change in Troy’s character, it symbolizes the moment where all his secrets and illusions catch up with him. He is forced to face the consequences of his selfishness and infidelity. Alberta’s death is not just a tragic event, it is the moment when Troy’s world begins to fall apart, exposing his deep regrets and his failure to truly connect with those who mattered most.

(7) With Alberta’s passing, Troy is left to raise Raynell, their child. This situation exposes his affair to Rose, resulting in a painful confrontation. Rose chooses to take care of the innocent child but makes it clear that her role as Troy’s wife is over. She emotionally withdraws from him, no longer willing to share the kind of intimate relationship they once had. This change deeply affects Troy, who begins to realize that his actions have cost him the most stable relationship in his life. The consequences also ripple out to his relationship with Cory. Troy’s controlling nature had already caused tension, especially over Cory’s football opportunities. But after Alberta’s death, Cory becomes more vocal in his anger and more determined to oppose his father. This growing conflict ends in a final argument that leads to Cory leaving the house. Troy, once a proud and authoritative figure, is left alone, having lost the respect and companionship of both wife and son. Alberta’s death also removes the only source of emotional comfort Troy had outside his home. Her presence allowed him to feel desirable and powerful in a world that often made him feel invisible. Without her, he can no longer run from his feelings of inadequacy and loss. He becomes more isolated, turning to conversations with death itself as a sign of his growing despair. In the end, Alberta’s death does not just mark the loss of a lover, it marks the collapse of Troy’s double life. It reveals the cost of his infidelity, the pain he has caused, and the emotional emptiness that remains. He is forced to live in the ruins of his choices, surrounded by silence and regret. Alberta’s death becomes a powerful moment of truth, stripping away illusion and exposing the broken man beneath Troy’s hardened exterior.

(VERSION I) (8) Troy’s inability to realize his own dreams becomes a cycle of disappointment that he inadvertently passes on to his son Cory, whose athletic potential is stifled by Troy’s fears. This father-son conflict captures the deep emotional toll racism has had on African-American families, showing how historical oppression does not end with one generation but seeps into the next through distorted forms of love and protection. The play also explores the subtle forms of discrimination that exist in the workforce. Troy’s initial position as a garbage collector performing only physical labor while whites drove the trucks points to the quiet yet pervasive boundaries that still kept Black men from advancement. His bold move to challenge that norm and become the first Black truck driver in his company reflects the beginning of change and resistance in the African-American community. Wilson does not limit the representation of African-American life to just struggle and bitterness. Characters like Rose provide a glimpse into the resilience, moral clarity, and emotional strength that often held families together in difficult times. Her commitment to raising Raynell, despite Troy’s betrayal, highlights the deep sense of responsibility and grace found in African-American households. Lastly, Fences is a deeply human story that reflects how African-Americans navigated a world that was often hostile to their ambitions, dignity, and dreams. Wilson’s work presents both the wounds and the willpower of a community fighting for a voice and a future, long before society was ready to fully acknowledge their worth.

(8) This loss becomes the lens through which he views the world and raises his children. His refusal to let Cory pursue football is more than just parental discipline, it is the product of fear, trauma, and a painful awareness of how little has changed for Black men. Yet, in trying to protect Cory, Troy unintentionally becomes the same kind of barrier he once fought against, thereby illustrating how oppression can be internalized and reproduced within families. The play subtly touches on the working-class experience of African-Americans. Troy’s confrontation with his employer over the unfair job distribution among Black and white workers marks a quiet but powerful act of protest. It reflects the growing awareness within the African-American community that they deserve fairness and dignity in the workplace, even if the road to equality is long. Wilson doesn’t paint his characters as mere victims; he presents them as complex individuals grappling with love, pride, fear, and failure. Rose, for instance, represents a stabilizing force in the family, offering emotional depth and spiritual fortitude even as she deals with her husband’s betrayal. Her endurance symbolizes the strength of Black women in holding their families together in the face of societal and personal hardship. Through the characters’ interactions, struggles, and growth, Fences shows that African-American life is not defined solely by racism but also by perseverance, complex identities, and a relentless pursuit of hope. Wilson’s portrayal is not only realistic but dignified, capturing a people determined to live with meaning in spite of adversity.

(8) Troy’s past serves as a metaphor for a larger communal struggle. He once had dreams of greatness, only to be held back by a system that did not value Black excellence. His bitterness becomes a barrier, preventing him from embracing the dreams of a new generation. This tension between past pain and future possibility creates a powerful emotional conflict within the family and mirrors the experience of many African-American households at the time. The domestic setting of the play is also telling. The Maxson home becomes a space where issues of race, gender, and class collide. The fence that Troy builds can be interpreted as both a literal and symbolic structure, meant to protect but also to divide. It signifies boundaries, both chosen and imposed, that shape the lives of African-Americans striving for stability and meaning. Wilson’s depiction extends beyond the personal to comment on labor and class. Troy’s struggle at work highlights how African-Americans were relegated to the most labor-intensive roles, yet were capable of challenging this status quo when given the courage and support. His promotion, though modest, is a milestone, a symbol of slow progress in a society resistant to change. What makes Fences particularly moving is its balance between sorrow and strength. Rose’s unwavering love and quiet resistance to despair reflect the resilience found in many African-American women who bore the emotional weight of their families. Wilson honors their role without reducing them to stereotypes. By the end of the play, the generational shift is clear. Cory’s decision to join the Marines and attend his father’s funeral indicates a complicated reconciliation with the past. Fences reveals African-American life as a continuum of struggle, love, memory, and resistance, offering a narrative that is as hopeful as it is heartbreaking.

(8) Troy’s personal history with racial discrimination in sports reflects a larger social reality. African-American men were often discouraged or outright barred from pursuing certain careers or ambitions, and these restrictions left lasting psychological wounds. His decision to stop Cory from pursuing football is grounded not just in authority but in fear, a fear born from experience that has taught him to distrust hope. Workplace discrimination is another critical lens through which Wilson examines African-American life. Troy’s insistence on driving the garbage truck becomes a bold act in a system that subtly relegates Black workers to menial tasks. Though it may seem small, this act of resistance signifies the gradual emergence of a voice that demands fairness, one that is no longer content to endure silently. The women in the play, particularly Rose, highlight another important aspect of African-American life: the emotional and spiritual labor often carried out by women. Rose’s strength is not in loud defiance but in her steady commitment to her family, even when betrayed. Her character challenges the traditional understanding of power, showing that survival and forgiveness are forms of strength too. Wilson also uses generational differences to emphasize the evolving consciousness of Black people in America. While Troy is anchored by the belief that the world will never change, Cory dares to believe in the possibility of a better future. This contrast captures a historical shift, from survival to aspiration. In Fences, Wilson does not offer easy answers or perfect heroes. Instead, he crafts a deeply human narrative of African-American life, portraying a people caught between a painful history and an uncertain hope. It is a portrayal marked by struggle, but also by courage, quiet victories, and an enduring will to move forward.

(9) The impact of colonialism is seen in the forced slave trade, where the strongest of African men were captured and shipped off to serve foreign masters. Their voices were silenced, their dreams stolen, and their lives controlled by those who held the keys to their chains. The poet laments the loss of freedom and dignity, as entire generations of Africans were reduced to tools of labor in lands they did not know. This subjugation didn’t just affect the body; it crushed the African spirit and distorted its culture. The poem captures how even in death, there was no dignity for the enslaved. Their corpses, rejected by the sea, were a tragic symbol of lives cut short and discarded. The Atlantic Ocean, which should have symbolized connection and exploration, becomes a watery grave filled with pain and abandonment. The emotional tone of the poem expresses the deep grief and betrayal felt by Africans. The once-proud continent mourns the broken past, where its people were manipulated and used for the benefit of foreign empires. Colonialism turned Africa into a source of raw material and manpower, draining it of its resources and strength. Lastly, the poem is not just a lamentation; it is also a reminder of the cost of colonial oppression. The poet draws attention to the spiritual, emotional, and cultural wounds that remain, urging readers to remember the pain, even as Africa tries to heal and reclaim its dignity.

(9) The continent is imagined as once youthful and blooming, but that vibrancy was short-lived. With the advent of the colonizers came violence and suppression. They introduced foreign rule through brute force, reducing proud nations to shadows of their former selves. The tools of domination, iron, fire, and chains, became instruments that erased African identity and imposed silence on its people. Slavery is portrayed as one of colonialism’s cruelest legacies. Africans were torn from their homelands, shackled, and subjected to hard labor in distant lands. The loss of freedom is vividly captured in the image of prisoners whose lives are now governed by the “jingling of goalers’ keys”. This metaphor shows how colonialism stripped Africans of control over their own destinies. Furthermore, the poem does not spare the gory details of this human tragedy. Death itself is dehumanized, as corpses of enslaved Africans are tossed into the ocean without ceremony. The Atlantic, far from being a symbol of exploration, is a graveyard where dreams are lost and lives are forgotten. The “putrid offering of incoherence” points to the senselessness of such loss. This poem is a powerful condemnation of colonial cruelty. It emphasizes the long-term effects of such oppression on the African psyche and landscape. Neto’s portrayal is not just an expression of anger but a solemn tribute to the resilience of a people who endured so much and still strive for liberation and self-definition.

(VERSION I) (10) These women, once vibrant and expressive in their sorrowful songs, are now gradually fading from collective consciousness. The poet speaks of “echoes,” of voices that once filled the air but now linger only faintly. This echo represents a troubling distance between the present and the historical pain that shaped the identity of the land. With each passing generation, the immediacy of the women’s trauma is reduced to a shadow of its former power. Their songs, once tools of resistance and endurance, now risk being forgotten altogether as time moves forward without remembrance. The persona of the poem does not accept this fading quietly. There is a strong undercurrent of urgency in the poet’s tone, a call to awaken memory before it disappears completely. He uses strong imagery—of shackled bodies, voiceless souls, and broken spirits—to remind readers of the harsh realities these women endured. Their song is described not only as a reflection of suffering but also as a source of communal strength. Through song, they preserved dignity and affirmed their humanity in the face of cruelty. The fear that these powerful expressions are being erased by time is what drives the poem’s emotional depth. A turning point in the poem comes with the idea of “communing with the yet unborn.” Here, the poet introduces a glimmer of resistance to time’s erasure by emphasizing the importance of passing down memory. Through storytelling and remembrance, the silence can be broken. The past must be intentionally preserved so that future generations do not lose sight of the pain and perseverance that shaped their heritage. Lastly, the poem mourns the silence left in time’s wake, but it also calls for action. It is a lyrical plea for remembrance, insisting that the women’s songs—though dimmed by time—can still be heard if people are willing to listen, remember, and retell. In doing so, the poem becomes not just an elegy, but a powerful act of cultural preservation.

(10) The poet vividly captures the tension between memory and oblivion. Initially, the women’s songs are portrayed as heartfelt expressions of pain and endurance—melodies that echoed across fields where they toiled and lamented their plight. These songs were more than expressions of grief; they served as a vital form of psychological survival and a way to maintain a shared sense of self amidst oppression. However, the poem laments how the relentless flow of time slowly wears away these memories, turning them into distant echoes barely perceptible to the present generation. This fading illustrates the danger that history might lose its emotional depth and meaning if not actively remembered. Yet, the poem’s speaker resists allowing these memories to disappear. Through evocative imagery of shackled souls and silenced cries, the poet insists on honoring the women’s legacy by recalling their struggles and the powerful role their songs played in sustaining hope. The persona expresses a deep yearning to reclaim these voices, recognizing that the survival of cultural memory depends on consciously passing it down. This is highlighted in the call to “commune with the yet unborn,” urging the living to transmit these stories so future generations will carry forward the resilience and spirit of their foremothers. The poem suggests that time’s erasing power can only be challenged through deliberate remembrance. Without such efforts, the women’s suffering and strength risk dissolving into oblivion, leaving only empty spiritual echoes wandering through the land. The closing lines convey a mournful yet urgent reminder that memory is fragile but essential. The poem becomes a poignant appeal for collective responsibility, emphasizing that the song of the women—though dimmed by time—must be revived through storytelling, remembrance, and respect to keep their history alive and meaningful.

(10) The women’s songs in the poem were originally expressions of deep anguish and resilience, offering them a way to cope with their harsh realities. These songs served as a vital connection to their identity and a source of solidarity within their community. However, as time moves forward, the vividness of these songs diminishes, turning into distant echoes that barely resonate with the present generation. This fading symbolizes not only the natural loss that comes with time but also the danger of forgetting the sacrifices and struggles that these women endured. Despite this, the poem’s voice strongly resists allowing these memories to vanish. The persona uses powerful imagery of chains, lost voices, and spiritual unrest to remind readers of the gravity of what was endured. By invoking the idea of “communing with the yet unborn,” the poem stresses the importance of passing down these stories through generations. It suggests that memory is not automatic; it must be nurtured and shared consciously to survive the eroding effects of time. The poem also highlights the emotional and cultural loss that results when these memories fade. The image of souls wandering in search of their songs conveys a haunting sense of absence and longing. It suggests that when history is forgotten, a community loses part of its spirit and identity. The fading of the women’s song is not just a loss of sound but a loss of connection to a shared past that shapes collective identity. Ultimately, the poem serves as a poignant call to remember and honor the past. It insists that time, though relentless, can be challenged by active remembrance and storytelling. The women’s voices may have grown faint, but through conscious effort, their songs can be revived, ensuring that their pain, courage, and legacy continue to inspire and educate future generations.

(10) The poem illustrates how these songs were more than just expressions of sorrow; they served as a powerful means of survival and unity. Through their music, the women communicated shared grief and upheld their dignity in the face of immense hardship. However, the relentless passage of time has dulled the clarity and immediacy of these voices. What was once a living memory becomes a shadow, a distant echo that struggles to reach contemporary ears. This decline reflects a broader concern about how history can be forgotten or ignored, especially the stories of those who suffered in silence. Despite this, the poet’s tone carries a strong undercurrent of resistance to forgetfulness. The speaker vividly recalls the pain endured by these women through haunting images of captivity and brokenness, insisting that their memory must be kept alive. The phrase “communing with the yet unborn” conveys the urgent need to pass on these stories to future generations so that the women’s experiences do not slip into oblivion. The poem suggests that memory requires active effort and cannot survive the natural erosion caused by time without intentional preservation. The imagery of wandering souls searching for their songs powerfully captures the spiritual and cultural loss that occurs when history is neglected. It evokes a sense of emptiness left behind when the voices of the past go unheard, highlighting the importance of remembrance as a way to honor the sacrifices and strength of the women who came before. Ultimately, the poem is a call to action, urging readers to defy the erasing effects of time through storytelling, song, and collective memory. While time may dull the sound of the women’s voices, it cannot silence them completely if we commit to keeping their legacy alive. Through remembrance, their pain, courage, and humanity continue to speak across generations.